In the angry days through which the world was passing, there was a ray of hope in this good-natured polyglot chorus of people who were not threatening each other, who smiled at strangers, who had collected in these shining white hills merely to enjoy the innocent pleasures of sun and snow….—American writer and Klosters resident, Irwin Shaw

From the lofty aerie of Parsenn’s Weissfluhgipfel, I see more than expected. South over the Alps’ sea of peaks, the familiar sail of the Matterhorn hoisted over distant waves. West to flat-topped Tödi, bobbing like an overturned boat. East to the Rinerhorn, Jakobshorn and Pischa ski areas breaking over Davos. And north to the Gotschnagrat, where skiers ascending by tram from Klosters first debark and Madrisahorn hovers on the horizon like an island mirage, shilling its own reputation for unhurried skiing and sun-drenched decks.

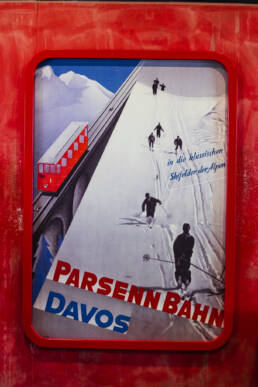

The legendary Parsenn Derby started here in 1924. One of Switzerland’s oldest ski races, it remained an important international competition prior to the formation of the modern Alpine Ski World Cup. Tipping my skis into the first drop floods the mind’s eye: the long climb up; sweat and wool sweaters; heavy wooden skis affixed with leather; mad schussing and even madder crashes along the 12km run down to Küblis on the Landquart River—the same watercourse that, decades later when she lived in anonymity in Klosters, film star Greta Garbo walked beside daily, adorned in a trademark hat.

These days it’s billed as the “Nostalgia Run” — and indeed I feel myself schussing past my own memories, rife with imagery of the cosmopolitan habitués who made Klosters what it is: a place where fame and fortune have lived quietly and untroubled for decades.

For the longest time, it seems, I skim the alpine sea, eyeing alabaster waves, down troughs and over crests before finally submerging beneath them. On both sides now, forested glades and chutes recall epic days spent chasing powder here. The slope mellows at the cluster of restaurants in Schifer, decks aimed west, on which I’ve consumed many a late lunch — the first time without even knowing I’d descended to Klosters from Davos, so closely are their capillaries intertwined on Parsenn. With no intention of gliding all the way to Küblis this early in the day, I make a quick deke to catch the Shiferbahn back to Weissfluhjoch, a 15-minute ride on which I was once joined by a well-known rock star whose ribald reflections seemed straight out of Spinal Tap.

This is how Klosters comes to you — in vignettes as fully formed as photos and film, posters and scripts.

Cradled in a rural sector of Prättigau Region, the romantic postcard village of Klosters stands in stark contrast to the bustling alpine metropolis of Davos but a few kilometers distant. Klosters (the name means “monastery”) dates to 1222, when Walser farmers settling this isolated valley were inevitably followed by monks who, also inevitably, inaugurated a village to feed them around the priory of St. Jakob. The current church, dating from 1492 but with windows more recently brushed by famous 19th-century Swiss painter Augusto Giacometti, is the last remnant of the medieval monastery. Standing on the small, cobblestoned church plaza above the village, I enjoy the preternatural quiet that speaks to Klosters mien — a less-charged atmosphere than larger, ritzier resorts. Peaceful even.

Still, its hospitality equals Switzerland’s best — think Zermatt and St. Moritz without the claiming or snobbery. Absent the spectacle, it’s every bit as luxurious, with compact Victorian and neo-classical hotels and an easy walk to anywhere. Add in Goldilocks isolation (not too much, not too little), and you have a crucible that has attracted those looking to escape attention since the end of the Second World War: during Hollywood’s Golden Age, mucky-mucks and celebrities that literally defined American royalty could be spotted nightly in Restaurant Chesa Grischuna, to this day one of the Alps’ best with its genuine feel and impeccable service.

The chic, chalet-style town of authentic traditions and locals who made even the most rarified guests feel at home also became the favored winter playground of real royal families — the Crown Prince and Princess of Denmark, the King and Queen of Sweden, and, of course, the UK’s ever-sporting House of Windsor. Newly crowned King Charles III has used über-exclusive Chalet Eugenia as a winter base for years, and, in the halcyon days when they were still speaking, Princes William and Harry learned to ski here. Charles has frequented Klosters so often (he canceled his annual ski trip this past winter for the first time in 45 years fearing injury before his coronation) that the Gotschnagrat cable car was christened “Prince of Wales.” To this day, many British skiers come to Klosters simply because of the royal stamp of approval.

Of course, it also has great skiing.

It was a 10-year-old Wilhelm Paulke — later geologist, snow researcher and German ski pioneer — who, along with fellow students of the international high school in Davos, first put skis to the slopes of Parsenn back in 1883. A decade later, Johann and Tobias Branger (brothers who legendarily taught themselves to ski at night to avoid peer derision) made a successful trip from Davos over the Maienfelder Pass to Arosa and back; the following year they guided celebrated British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle along the same route. Conan Doyle’s humorous send-up of his trip in the magazine The Strand proved providential to the area’s development. In 1895, four British tourists attempted to follow in his tracks; two turned back at the summit while the remaining pair took a wrong turn en route to Arosa, spending a cold night in a shepherd’s hut before descending through forest to Küblis. Fortuitously, it was recognized that if one could reach the summit from one town and descend to several other hamlets, it was clearly a crackerjack ski area.

That’s on my mind while descending off-piste under the Gotschnagrat cable car — perhaps the toughest challenge in the entire Davos-Klosters colossus. Once upon a time a marked itinerary, skiers are now largely discouraged from it. Perhaps because Brits hoping to causally bump into their once-Prince tend to cluster in the Gotschna region during his usual January sojourns, typically a snowy — and avalanche-prone — time in which this particular slope doesn’t lend itself to a Keep Calm and Carry On ethos. It’s probably best that they steer less-experienced holidaymakers toward the Köbel bump run, the gentle blues of Gruobenalp chair and Parsennmälder T-bar, or the marked off-pistes in the Drostobel and Chalbersäss valleys.

Though I can recommend them all, I also find the valley its own draw, with quiet walking paths, horse-drawn sleigh rides, tobogganing, snowshoeing and an extensive cross-country ski network that, collectively, seem to roll the clock back to simpler times. Klosters, in fact, takes its cross-country seriously, even featuring langlauf-designated hotels.

The 15km circuit that passes the village of Monbiel is charming, and the short climb to scenic Alp Garfiun always worth the effort. It’s also worth the effort, no matter where you’re staying, to poke your nose into the town’s most celebrated accommodation.

I have the good fortune to not only stay a few nights at the Chesa, but to be guided through both structure and story by its new owner, one-time television journalist and now entrepreneur Astrid von Stockar, whose passion project is to protect the hotel’s heritage and many salient details. With a sparkle in her eye, Astrid flies through the restaurant, pointing out original chairs, benches with cushions held by leather straps — even the first china — for each of which she has sourced people capable of doing restoration or identical replacement. Some she has taken on herself; stressing over how to fix the aesthetic affront of too-short curtains, she discovered enough original fabric turned up in the hems to lengthen them. When she identifies King Charles’s favorite table — the round one in the corner with windows on both sides — I realize I’ve sat there with friends. Finally, she shows me the spot from which an old grand piano was moved; we follow its trail downstairs to where it now occupies space on the legendary bar’s famous dance floor, scene of much merriment and tales of Gene Kelly tap-dancing on the bar. Astrid even cracks the door to the Chesa’s famous two-lane bowling alley, added in the 1950s.

Upstairs again, sitting to dine, it’s impossible not to register the woodwork, paneled ceilings and decor as eye-drawing art intended to be seen from this angle. While the Chesa indulges diners with classic old-world service, the current incarnation is an award-winning treat; it’s hard to deny an amuse-bouche of smoked local trout on a sliver of toast, the famed Chesa salad — a sort of Caesar-meets-alpensensibility — or classic beef tartare.

For Astrid, who has come here since she was a child, the Chesa “is the heart of Klosters,” and like all hearts, in need of tending. For someone whose work once turned on storytelling, the Chesa and its guestbook represent hundreds of stories braided into a larger tale of the character of Klosters and its nexus of history — like the small painting with which a young Winston Churchill bid adieu, adding “My only regret is having to leave this wonderful place.”

Beyond those who visited often, Greta Garbo’s longstanding residency in town became an identity statement: if the notoriously publicity-shy star felt safe here, so could anyone. Everything was on the down-low and visitors adopted a humble demeanor; they didn’t brag, show wealth, or smash champagne bottles. Even today, Switzerland is a place where globally famous folk famously find refuge (think Tina Turner and Shania Twain), something for which Klosters in the 1950s was both bauplan and microcosm.

On the mountain again, I circle the Gotschna, rip a few of the Parsenn’s wide-open main runs (sehr schnell, of course), and tackle the Weissfluhjoch. Finally, I ascend the Weissfluhgipfel for one final Nostalgia Run to Küblis, riding the train back to Klosters and hoofing it the three minutes back to the Chesa with my skis over my shoulder.

Changing quickly, I head down the street to meet a friend at Hotel Wynegg, a Klosters staple for some 140 years. A traditional place with youthful spirit, the Wynegg’s restaurant is small and intimate — but also popular and packed. It’s a place where home-style cuisine and regional specialities meet fresh, innovative ideas — like bread served with passion fruit, mango and thyme butter, “fake” snails (sautéed beef cubes with herb butter) and several variations of pizokel—a kind of local pasta made from flour, eggs, milk and yoghurt; I have the Älper version with bacon, onion and cheese, served with homemade apple purée.

Talk at dinner begins with the New Year’s Day piglet race and how much cherry liqueur was consumed before turning to how the town celebrated its 800th anniversary in 2022, with projects that included looking at skiing through historical period costumes, a theatrical take on jurisdictional evolution (apparently not as dull as it sounds), a 57-meter climbing wall affixed to the concrete strut on Klosters’ famous bridge, and new commemorative bells for the church, hoisted into place on pulleys by enthusiastic schoolkids.

It all speaks to something visible in every corner of Klosters: enduring community. It’s a quality that attracted several Americans to settle here after experiencing the traumas of war — like the “King of Klosters,” writer Irving Shaw. Son Adam Shaw explained his father’s attraction in the opening essay of Fabrizio D’Aloisio’s 2022 coffee-table history Klosters: “In those days, skiing was as much a voyage as a sport, and that appealed to the old man. Imagine growing up dirt poor in Brooklyn before the Great Depression. Imagine landing at Normandy in 1944, and liberating Dachau concentration camp. Then imagine standing on top of the Gotschna on skis, with [your] newly built chalet visible down in the valley.”

Klosters offered peace, solace and camaraderie to a generation. A balm that also happened to come with great skiing.