Banff – Canada’s signature tourist destination and most distinguished resort icon-hasn’t gone anywhere. Indeed, it’s grander than ever.

A brief history of then Canadian Rockies: During an era of vigorous tectonic activity during the Cretaceous, 15,000 feet of limestone sediment buckles up in the continent’s interior like so much scrunched carpet. Repeatedly glaciated, it eventually yields a 1,500‑mile north‑south spine of postcard peaks skirted in forest, framed by ice, and constellated with azure lakes.

For millennia, First Nations hunters are the sole human occupants. Then European settlers, spreading west across the continent, declare a country. A railroad is required to hold it together. Crossing the Rockies is the biggest challenge to construction but also the biggest draw; cue a bailiwick of National Parks, grand hotels, intrepid guests, Swiss guides, famed climbing, and storied skiing.

Today, 125 years later, not much of that historical equation has changed. And neither has the single epithet tying it together in the collective consciousness: Banff.

Today, 125 years later, not much of that historical equation has changed. And neither has the single epithet tying it together in the collective consciousness: Banff.

Growing up in the 1970s, Banff hovered as a Holy Grail for the eastern Canadian skier. The resort triad of Mt. Norquay, Sunshine Village, and Lake Louise comprised a mecca which, prior to a shift toward coastal giant Whistler, drew most ski bums west. A Colorado of the north. I was one of those wide-eyed acolytes, spending the winter of 1977-78 groveling—as ski bums do—at the low end of the food chain amidst geologic splendor. Though living in a dingy basement did little to diminish the superlatives in my letters home, any experience of the town’s signature comforts was necessarily curt. Lacking opportunity since to turn my significantly more experienced (and aged) eyes to what Banff has to offer, I returned this past March to view things through a different lens.

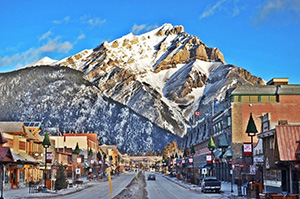

In the intervening years, Banff had retooled, expanded and modernized in ways that haven’t compromised its historical cachet, a gravitas more relevant than ever. So much so that the Grand Dame now seemed to me more of a fresh‑faced débutante—perhaps more world-wise than most, and garbed in a traditional gown. I start my re-acquaintance where it all first began—atop Norquay, the venerable “local hill” whose superb overviews offer a kind of orientation no map can deliver. Looking south from the historic Tea House at 6,900 feet, with its undulating art-deco roof featured in so many period photos, banff the Banff townsite sits tucked against the hillock of Tunnel Mountain under the stern flanks of Mt. Rundle, from whose notched summit snow jets stream into gunmetal sky.

To my left is Mt. Cascade, a tilted‑cake countenance that frames all views down Banff’s main street. For a town hill, Norquay was as bad-ass as it got in those days, other than beginner flats at the bottom, it was all steep cones of forest-covered talus and interconnecting gullies that avalanched with regularity. And though new lifts and a major addition of intermediate terrain have since been added, Norquay’s original GS-style pistes quickly remind me of the mountain’s substantive race heritage. Not to mention its freestyle chops—as the massive bumps on infamous Lone Pine off the North American Chair attest. This double-black plunge poses serious challenge even to advanced skiers (or teenaged ski bums), especially when, like today, those bumps are icy beneath an inch of soft powder.

Descending—in a now more accomplished manner—I recollect the apocryphal tale my friends and I gleefully traded of the unfortunate skier who fell at the top and slid 1,300 vertical feet in a gold-lamé one-piece that was then employed as his body bag.

The silliness of that untruth notwithstanding, Norquay doesn’t quite draw the snows of Banff’s other two hills. Although there’s serious steep-and-deep potential when it’s on—typically in early or late season—it’s more of a cruiser’s dream, as a few subsonic laps on the Mystic Chair emphasize.

Returning to the Tea House I gaze back across the valley, past the palatial train station marking one of the most important stops on the continent, to follow main street out toward Cave and Basin hot springs, the primary reason for building what my eyes fall last upon: a grand spa hotel known as the Banff Springs.

Built at the behest of Canadian Pacific Railway magnate William Cornelius Van Horne and opened in June 1888, the Banff Springs Hotel has survived fires, redesigns, renovations, and a half‑dozen architects to stand as the finest example of Scottish Baronial architecture in North America, a paean to post‑Renaissance opulence. A trip to Banff isn’t complete without a visit to its iconic hotel.

I check into a corner room with views down the Bow Valley between Mts. Cascade and Rundle in one direction, and up the Spray Valley between Rundle and Sulphur Mountain in the other, an overlook that includes cross-country ski trails braiding over the renowned golf course. These were the peaks on which I did my first climbing and backcountry skiing, memories that now glue me to the windows; I literally force myself out for a walking tour.

The hotel’s colorful history is on display everywhere, and while heavy on the head-of-state and celebrity traffic that has graced these halls over its 125-year life—Marilyn Monroe famously recuperated from injury here in ’53 while filming River of No Return (see Beauty in Banff, page 28)—I’m more interested in the building’s art and architecture. Wandering labyrinthine passages to poke into famed spaces like the ballroom, conservatory, lobby, Mount Stephen Hall and Rundle Lounge—with its signature afternoon tea service—while contemplating archways, stairways, tapestry and carpet, is considerably more enchanting as a guest than scuttling through them as a floor cleaner, a job I held here for a few months back in the day. Later I’ll stroll the expansive terrace, where Swiss mountain guides met clients before embarking on hikes and climbs; I’ll take in the continental ambiance of the wine bar and newly renovated Waldhaus restaurant; and I’ll enjoy a traditional—and truly massive—breakfast buffet in the spacious Bow Valley Grill (formerly the Rob Roy Room, replete with famous kilted ghost). For the moment, however, I’m focused on a sector that I have never actually seen; and when I do, it literally drops my jaw.

Like the building it dwells in, the Willow Stream Spa is a multi‑story collection of stunning spaces connected by stairwells and passages. Some—the archway-framed long pool and skylight‑capped round pool—feel like giant solariums, mountains pouring in through the impressive acres of glass that girdle much of the hotel’s base. Outdoor hot pools deliver same.

Fireplaces and plush armchairs adorn sitting rooms. Tiles mosaics dance before your eyes. And water gurgles everywhere. You’re contentedly zombified before you even begin any treatment and you know this much: the spirit of the European spa hotel is alive and well in the Canadian Rockies, the reasons for situating it here more than clear—even if you have yet to venture into town or test the waters of Sulphur Mountain’s Upper Hot Springs or Cave and Basin.

But of course you will do that, perhaps stopping along the way to visit the intriguing Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies and, marrying what you will learn of the past to the present, dining later at the bustling Bear Street Tavern or its upstairs cohort, The Bison, both excellent establishments (the carpaccio at the latter is to die for, the signature pizza and calzones of the former celebrated roundly—usually with a hoppy IPA) emblematic of the town’s upscaling, local food sourcing and enviro-consciousness.

Wonderful as this all is of course, it’s mere noise against a background of exceptional skiing. Several days later, in clearing conditions, I stand atop the Continental Divide Chair at Sunshine Village, the ski area I frequented most when I lived here. From this vantage it seems little is different—the view across a glaciated jumble that includes Mt. Assiniboine, the Rockies’ de facto Matterhorn; the Euro‑like gondola access that delivers skiers from a parking area below Mt. Bourgeois to the odd concatenation of buildings that include a warden’s cabin, Mad Trapper Saloon, and domineering Sunshine Mountain Lodge, Banff’s only ski-in, ski-out hotel. And yet much, in fact, has changed.

The lodge is newly expanded and renovated, its Nordic chic a welcome change from Rockies funk; the ski area itself has virtually doubled in size, with so much new terrain it has taken days to suss out the best circuits through a mountain realm as convoluted as the Banff Springs. And now, after a morning cruising familiar pitches off Strawberry, Standish, and Wawa chairs, then powder runs on always reliable TeePee Town, I’m about to experience something else I’d been deprived of in those heady days past. Only steps away is the gate to Sunshine’s test-piece, Delirium Dive, a high‑alpine amphitheater accessed via metal catwalk that was closed for decades until Parks Canada figured out how to run avalanche control in this vast drainage to make it safe.

When it opened in the 1990s “The Dive” legitimized the Canadian Rockies in the international annals of big‑mountain resort skiing—not that it wasn’t already on the ledger with Lake Louise Ski Area. I’d spent a couple days at Lake Louise en route to Sunshine, eschewing the expansive front apron of Whitehorn Mountain which faces the eponymous geographic icon in favor of its backside basins, currently reveling in the word‑of‑mouth spotlight of a couple of good snow years. I found powdery bowls, tree shots, pillow lines, and few people. Then, from the area’s historic Temple Lodge, I ski toured the easy but stunning seven miles into historic Skoki Lodge, the first facility built specifically to cater to ski‑tourists in North America. Arriving at the varnished-log structure nestled deep in a river valley beneath majestic peaks felt like time travel, a notion confirmed when I crossed the threshold into a space virtually unchanged from the day it opened in 1931. Wooden skis, poles, and snowshoes adorned a large stone fireplace and the aroma of fresh-baked bread and homemade soup stirred the air.

After a night at Skoki, I made my way back to Lake Louise through a foot of snow and bunked at Deer Lodge, enjoying its fine restaurant (one of the sleeper hits of my trip), strangely angled halls, and unique circular drawing room with its massive bay windows, enormous stone fireplace, anachronistic collection of animal heads, and walls adorned with historic photos from the golden age of Canadian mountaineering—a pastime that got its start right across the street at venerable Chateau Lake Louise.

Beginning in 1889, Van Horne’s Canadian Pacific Railway imported Swiss guides to develop a trail system that would radiate deep into the mountains from Lake Louise. From the simple log cabin erected here in 1890 to act as day shelter for hikers and climbers, through the inevitable devastating fire, new wooden lodges, more pernicious fire, and eventual expansion and architectural shifts grandiose enough to garner the moniker “chateau,” coalesced a 550-room structure that today ranks among the most celebrated in global resortdom. Neck-craning through the soaring, decorous spaces of the Glacier (1987) and Mount Temple (2004) wings, it’s hard to imagine such humble beginnings. The site choice for Chateau Lake Louise, however, remains indisputably iconic.

More so even than its sister hotel the Banff Springs, the Chateau is defined by its views. From the second I passed into the grand lobby, a glance through the soaring windows of the Lakeview Lounge—familiar from colorful Canadian Pacific Railway posters of yore —returned it all to my senses immediately: framed by Mts. Victoria and Farady, and backed by the blue teeth of the Victoria Glacier, was the quintessential, forest-encircled, ice‑covered icon. On it was being conducted a wedding, skating, cross‑country skiing, and a horse‑drawn sleigh ride. Snowflakes filled the air. It was a postcard scene to punctuate what had been a postcard “reunion” tour, one whose end was in sight.

At the top of Delirium Dive, snow squeaks under my skis; cold, fine-grained powder that makes an argument for Sunshine’s perennially-debated slogan of “Canada’s best snow.” Having sent my bag down ahead, I’ll tip into The Dive, ski some astounding terrain, then make the familiar five-mile run down “Banff Avenue” to the parking lot. Along the way will be powder, memories, history. And everywhere around, those mountains, thrust up all those eons ago.

Related Posts

Nothing found.