In the pantheon of first-rate photographers, some might say Ansel Adams was to nature what Slim Aarons was to haute society. But what if Aarons was actually both? Moreover, what if the two star shutterbugs, both American, both now gone, were actually more alike than one might, at first, deduce?

Aarons — whose photographs remain the definitive ode to a bygone jet set, an all-encompassing photo album of the rich at play — was big on “mise en place,” according to his daughter, Mary Aarons. His rule of thumb, she explains as we sit to talk, was that the “entire setting should tell the story of the place or person.”

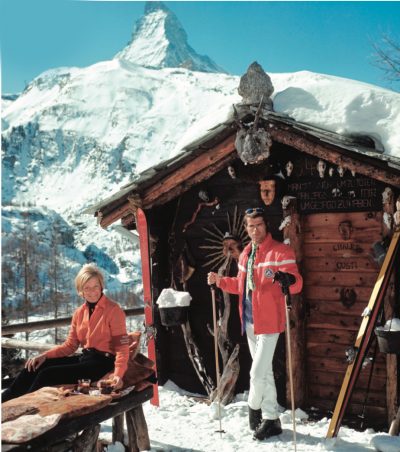

And among those settings? A plethora of photos set amongst the planet’s most fabulous wintry abodes: photos that rank among her own personal favorites. Though lesser known, perhaps, than some of her father’s most enduring photos — images like Poolside Gossip of two socialites exchanging intel in Palm Springs, or Kings of Hollywood in which Clark Gable and friends laugh it up in black tie in Beverly Hills — the snow-speckled photos continue to cast an allure unto themselves.

Mary Aarons, the keeper of her father’s legacy, generally favors “the landscapes,” as she calls them. In that respect, her father covered the gamut, his many “ski-lift” tableaux (from Gstaad to Aspen) acting as a foil to the “beautiful boats… the beach umbrellas” that he also endlessly, tirelessly, chronicled from the Côte d’Azur.

What united the photos, both hot and brrrr? “They were,” his daughter muses now, “photos of happy times.”

Happy, yes, but also all-powerful. Aarons’ snow photos, one could argue, did as much as anyone ever has to make the world of skiing glam.

He “extracted everything that was cool and chic” about old money in the 1960s and 1970s, is how style-watcher Simon Doonan describes Aarons’ work for magazines like Life and Holiday back in the day, then amplified further in Aarons’ now classic books of photography, such as Slim Aarons: Once Upon A Time. Doonan went on: “He left behind the dusty mumsiness of it and make it look incredibly crisp.”

Slim Aarons’ mountain photographs, in particular, offer nothing but charm and nostalgia and, yes, crispness. The pants were tight, the poles were straight, and the sweaters were as bright as M&M’s. In Aarons’ world of après-ski, the champagne flows ever freely and the frisson of fun is never far.

Among the most famous of these snaps is one he took of William F. Buckley, a godfather of conservatism, getting jolly with John Kenneth Galbraith, a celebrated economist who held a similar command in liberal circles. The photo reveals them laughing it up in the town center of Gstaad. Score one for political bipartisanship! If nothing else, the image shows that skiing was to bring these two disparate men together.

Other winter wanderlust shots include one from 1963 titled Winter Suntans (in which a group of women are shown blithely reclining on the Gstaad snow, rugs covering their knees) and another dubbed Winter Wear (in which two ‘60s beauties are working furry go-go boots in the Italian ski resort of Cortina d’Ampezzo). A bittersweet photo taken at Verbier shows skiers admiring the view across a valley of clouds. Another taken in Vermont depicts students from a prep school making spirited tracks in the snow near Spruce Peak. And on it goes.

Possibly the most amusing of Slim Aarons’ photos — one that suggests his tongue was firmly in cheek — is an image dubbed Skiing Waiters: Three servers ski through the trees, each shown carrying, in turn, a bird on a tray, a menu, and a bottle of wine chilling in a bucket. So droll.

That the intrepid photographer was drawn, again and again, to the snow is no mere accident. He came by it quite naturally, growing up as a simple New Hampshire boy. Cross-country skiing was his forté, and he later became an associate of the International Skiing History Association, as was noted in some quarters when he died in 2006 at age 89. Post World War II, when skiing became the hot new sport and the Social Register was an actual thing, Aarons was on the scene, Leica Camera swinging from his neck. Right place, right time, right man.

So influential did Aarons become that he’s said to have been the inspiration for Jimmy Stewart’s character as the ardent voyeur in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 classic, Rear Window. (When approached by fans, Stewart is said to have quipped: “No, I am Slim Aarons.”) But what became the photographer’s primary mission — snapping “attractive people who were doing attractive things in attractive places” — was a reaction to what he’d seen in the aforementioned war. “After you’ve seen a concentration camp,” Aarons said, “you really don’t want to see any more bad things.”

Dispatched as a combat photographer in his 20s, George Allen (Slim) Aarons saw both battlefields and sieges, and was himself wounded during the Battle of Anzio as the Germans blew up a dock along the Italian beach. Aarons lost a twin brother in the war; he was also granted a Purple Heart.

He saw himself as a “photojournalist” and a “storyteller.”

Clearly, he never looked back. Hell-bent on dreamier adventures, after the war he worked as a stringer in New York and Los Angeles, and then as a regular correspondent for LIFE, going on to photograph everyone everywhere: C. Z. Guest standing erect and ice-cool as the hostess of Palm Beach. Babe Paley at her cottage in Jamaica’s Round Hill. The Duchess of Windsor dancing with her Duke in the winter of their lives. Such a zelig figure was Slim Aarons that during Britain’s Ascot races, when Aarons was accidentally knocked down by guards, he was rescued by none other than Prince Philip. “Slim,” the prince said, “what the hell are you they doing to you?”

Of his technique, his daughter tells me, “His pictures captured the soul of the individual through their eyes. It’s a trick he stole from Leonardo de Vinci (being self-taught in the Old Masters).” Yet another technique — one that’s more than manifest in his ski-world portraits — is something pointed out recently by art photographer Tina Barney. “I was always interested in the way he photographed very few close-ups,” she said.

“He deliberately stood far enough away from his subjects so his camera captured their surroundings, their backgrounds. His best portraits were statements.”

It’s a philosophy that brings full circle, indeed, the worlds of Aarons and, yes, Ansel Adams, even if the latter is sometimes considered more of an “artist” than the former. Adams, whose pictures are so poignant that they continue to be an inspiration for the conservation movement, once famously mused: “You don’t take a photograph; you make it.”

Wasn’t Aarons doing just that? When both giants took a photo, they didn’t just capture a scene, they captured a feeling.

Something else that Adams said that also amply applies to Aarons: “A good photograph is knowing where to stand.” Both, clearly, were the kinds of photographers who’d climb over whatever what needed to be climbed, and trek whatever number of hours needed to be trekked, to get “the shot.”

Asked if she sees her father as an “artist,” Mary Aarons shrugs off the notion. She says he saw himself as a “photojournalist” and a “storyteller,” above all. She adds, once again:

“Every picture told a story.”

SHINAN GOVANI