The Colorado Olympics that Weren’t

How Colorado won, and lost, the 1976 winter Games — and why it matters today.

By Cynthia Psarakis

On Feb. 4 , 1976, an expectant crowd packed shoulder to shoulder into a chilly open-air stadium for the opening ceremony of the Xii Olympic Winter Games. Performers and dignitaries alike took the stage against a backdrop of majestic, snowy mountains, and runners clad in red and white sprinted up a long flight of stairs, touching torches to massive cauldrons and setting them ablaze with the Olympic flame. Country by country, athletes marched in the parade of nations — that moment of glory guaranteed to every Olympian before dreams are fulfilled, or dashed — the Greek athletes first by tradition, and those from the host nation last.

Those final athletes were Austrian, but they were supposed to have been American. And the stadium — Bergisel, near Innsbruck— should have been Mile High, home of the Broncos. Six years earlier, the International Olympic Committee had welcomed Denver, Colorado, into the exclusive fraternity of Olympic hosts, but in the end Denver gained an entirely different distinction: It became the only city in the history of the modern Olympic era to win the Games and then give them up.

The story begins in the 1960s, when a coalition of Denver’s business and civic leaders began preparing a bid to bring the Olympics to town. Colorado’s then-governor, Republican John Love, lent his enthusiastic support to the effort, appointing skiing trailblazer Merrill Hastings as the state’s Olympic coordinator. Operating as the Denver Olympic Organizing Committee (DOOC), the group spent the better part of the decade devising a $14 million plan to transform the city into the kind of winter-sports mecca capable of hosting an Olympic competition.

On May 13, 1970, at the 70th IOC Session in Amsterdam, the committee convinced the IOC of the validity of its plan. The Mile High City was officially anointed the site of the 1976 Winter Games, and seemingly the entire state of Colorado greeted the news with a wave of boosterism and civic pride.

Then it all began to fall apart.

The first flaw in the plan should have been the most obvious: Denver is not, strictly speaking, located in the mountains. It lies on the eastern slope of the Continental Divide, to the east of even the foothills of the Rockies. Yes, it sits at 5,280 feet, but what the city has in altitude it lacks in terrain and, more importantly, snow. But in its quest to convince the IOC that Denver was an ideal choice, the DOOC had placed all of the sporting venues — none of which actually existed at that point — within less than an hour’s drive of the city.

Among the sites was Mount Sniktau, the proposed site for the alpine events, which is not a skier’s mountain, and doesn’t have reliable snow cover. In the nearby community of Evergreen, where the Nordic events were to be staged, residents learned that the competitions would literally run through their backyards(and the grounds of at least one school), and formed an organization called Protect Our Mountain Environment in protest.

As the complaints mounted, the DOOC recalibrated. The alpine events headed west to Vail, which had abundant snowfall and a desire to host, but was still a relatively young resort. The Nordic events were moved even farther to Steamboat Springs, where there was, at least, a ski jump already in place.

This solution became a new problem. From Denver it takes nearly two hours to drive the 100 miles to Vail; the trip to Steamboat Springs, 156 miles away, takes a minimum of three hours. The promised hour-long jaunt to fully half of the events — and the sexy ones, at that — had ballooned into an unmanageable commute over mountain roads and passes not designed to handle a great volume of traffic.

Colorado’s ski industry was still in its infancy at the time — Vail was only entering its 10th year of operation — and the idea of promoting the largely unsullied Rockies as a winter playground for the world triggered another round of environmental angst, along with a new fear: Once you invite the hordes in, it’s hard to keep them out. The sprawling Olympics seemed to herald the onslaught of unchecked development across the state.

But for all the hand-wringing over environmental concerns, the mushroom cloud of questions looming over Denver’s Olympics centered on “how,” not “if.” After all, no city had ever turned down a chance to host the Games. It simply wasn’t done.

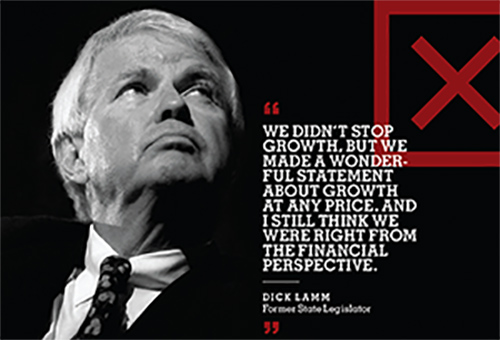

Enter Dick Lamm, who wasn’t familiar with that particular rule of international etiquette. Elected to the state legislature in 1967, Lamm sat on the committee charged with auditing the state’s finances. When the issue of the Colorado taxpayers’ share of the Olympic tab — $5 million — came up, that committee began asking questions. The original $14 million total budget had gone the way of the 60-minute drive, more than doubling to $35 million. And Lamm had noticed something even more troubling: No city had ever made money on the Olympics, and in fact most had been left with a sizable debt. “The first thing on my mind was the financial vulnerability,”he recalls.

“Look, if a city in Japan hosts the Olympics they’ve got the whole financial structure of the country to support that, but Colorado was a small state.”

Lamm channeled his uneasiness into action,forming a statewide coalition of regular folks turned activists who dubbed themselves Citizens for Colorado’s Future. In short order and with shorter funds they led a successful petition drive to add an amendment to the state’s constitution outlawing the use of state money for the Olympics; the DOOC fought back with an extensive PR campaign. On Nov. 7, 1972, it all came down to the voters.

It wasn’t even close. A whopping 60 percent of the votes were cast in favor of the amendment. Without state funding there could be no federal funding, and without either there could be no Olympic Games in Denver. Developmental, environmental, and financial crises averted.

But of course, that wasn’t the case. Citizens for Colorado’s Future may have put Denver’s Olympic dreams on ice, but it did nothing to stop the rampant growth that so many feared would follow the Games: The state’s population in 1970 was just over 2.2 million; by 1990 it had grown by half, to just shy of 3.3 million. Much of that growth was concentrated along the Interstate 70 corridor, dotting the once pristine landscape with a jumble of condo developments, strip malls, and ski resorts. The interstate became — and remains — the bane of virtually every mountain-loving Coloradan’s existence, home prices spiraled out of sight,and the granola crunchers and ski bums who had fought to keep Colorado wild found themselves shut out by powerful developers who gobbled up all the best land for private resorts catering to affluent ski tourists — or they became real-estate agents themselves.

People began to wonder if the state had been so smart to turn down the Games after all. Perhaps, the reasoning went, it would have been better to view those millions of taxpayer dollars not as a risk, but as an investment in the state’s infrastructure. Combined with the $15-plus million Uncle Sam had been prepared to kick in, the Denver-Vail stretch of I-70 could have been re-engineered to accommodate the impatient mass of cars that now clogs every lane — or even better, supplemented by some form of mass transit. Several of the proposed venues were built anyway, but without the impetus of an impending Olympics they took much longer to come about (Beaver Creek, conceived as the alpine site and now host to World Cup races, didn’t open until 1980), resulting in higher startup costs and lost revenues. In some corners there were whispers that Colorado had passed up a golden opportunity.

Even Lamm entertains that notion. Sort of.

“I’ve heard that many times,” he says, “but looking back, how would we ever know? We didn’t stop growth, but we made a wonderful statement about growth at any price. And I still think we were right from the financial perspective.”

He’s got some agreement from an unlikely source: Denver’s current mayor (and newly minted gubernatorial candidate), John Hickenlooper.

“If I could go back to 1972, I think I probably would have voted against it myself,” Hickenlooper says. “I don’t think the city and the state were ready and could have accommodated the Games without too much risk for the reward.” But don’t mistake hindsight for Hickenlooper’s current perspective. “I think now the state could benefit dramatically from the Games,” he adds.

Which brings us back to the future, and to the question that began burning this summer: Would Denver again throw its hat into the rings?

It certainly looked like it, albeit not officially. As Chicago nervously twiddled its thumbs waiting for word on its bid for the 2016 Summer Games, speculation began that Denver would plead its case for the following Winter Olympics. The United States Olympic Committee wasn’t having it. Maintaining that its focus was on Chicago and 2016, the USOC effectively closed the door on any American bid for 2018. Then the deadline for submissions passed, making the question moot. And so all eyes are now turning to 2022.

No one really wants to go on the record with a bold affirmative. Olympic politics are delicate and mysterious, especially for a city that has already spurned the IOC once. But it is safe to say that Denver has been positioning itself as a city that is more than capable of an Olympic-size challenge.

As Hickenlooper notes, “The [2008] Democratic National Convention was one of the best national political conventions in a long time. We hosted the 2009 Sport Accord, the U.S. Curling Championships, the U.S. Boxing Championships, and the Rugby Cup — in 2012 that’ll be an Olympic sport. We’ve demonstrated that we can be a remarkably high-value venue for hosting Olympic-caliber events.”

Spearheading such efforts is the Metro Denver Sports Commission (MDSC), a nonprofit devoted to promoting the city as an international sports venue par excellence. By all accounts it is doing a fine job, working toward a potential Olympic end by building relationships with the IOC, the USOC, and the ski resorts that will, inevitably, be tapped for the skiing events. MDSC founder Rob Cohen has even reached out to Dick Lamm, asking him to be a part of the process and to ask the tough questions so that the next time Denver submits an Olympic bid, it will be one that Lamm and those of a like mind can support. For his part, Lamm says he’s willing to keep an open mind.

It seems like a stunning change of heart for the man who mobilized a citizen’s army to derail Denver’s Olympic dreams in 1972. But it has been nearly 40 years since that fateful vote, and a lot has changed, not least the Olympics themselves. When the DOOC was formulating its optimistic plans, it was common for public funding to comprise a significant chunk of the operating budget, and for cities to invest heavily in constructing brand-new venues for sports that have limited appeal outside the Olympics (we’re looking at you, speed skating). And the Winter Olympics were hardly a ratings juggernaut at the time, meaning that revenues from the broadcast rights were far lower, if they materialized at all. But aside from money for major infrastructure projects — where the use of public funds can be justified by the benefits to the community — most of the money needed to stage the Games now comes from private sources, ticket and merchandise sales, and TV broadcasts that attract significantly higher numbers of viewers.

Cities have also become more savvy about the process. Since Los Angeles set the example in 1984, it’s become routine for communities to adapt or repurpose existing venues; where new facilities are necessary they’re often designed with future use — and income potential — in mind. Organizing committees no longer court only the IOC; they also employ sophisticated marketing campaigns to ensure sufficient funding and support from the private sector. And when public money does come into play, it’s used for long-term infrastructure development and improvements.

This evolutionary process has resulted in an approach to hosting the Olympics that is worlds apart from the DOOC’s failed effort, and one that Denver’s movers and shakers have clearly embraced. But it still doesn’t solve Colorado’s geographic Achilles heel: the sheer physical distance between the host city and the snow sports venues. That’s why the MDSC has been paying careful attention to the two most recent Winter Olympics.

As Cohen explains, “Torino and Vancouver had very similar issues in terms of distance, where the outer venues were 1½ or even 2½ or three hours away. We’ll take the best practices from those Games and apply them to our plan.” As for consternation over I-70, Cohen says, “People don’t like my answer, but I-70 is fine for hosting an Olympics. Both Torino and Vancouver will have essentially taken a two lane highway and turned it into a four-lane interstate for [their] Games. You can control the rest of the process with permits and buses, etc., similar to what they’ve done.”

Hickenlooper concurs. “It’s not uncommon now that you need a big enough city to have an arena that can host an Olympics, but those big cities aren’t going to be right next to ski areas. I think other cities are already addressing these issues. Look at what happened with Salt Lake City: They got their light rail system in place. People here have talked forever about having a rail line up to the mountains to reduce the stress on I-70. Hosting an Olympics is something that would help create that partnership among federal, state, and local governments to enable that to be built.”

So all the pieces for Colorado to repair its legacy in the Olympic pantheon seem, at least for now, to be falling into place. It remains to be seen whether the USOC will trust Denver again; Bozeman in Montana and the Reno/Lake Tahoe area have already begun to lobby for 2022. And the IOC may be less forgiving still — with Canada, New Zealand, Spain, and Switzerland all rumored to be considering their own 2022 bids, Denver will face some stiff competition. But while Cohen acknowledges the challenges — “1976 is part of our history; we’re not going to run from it,” he says —he also sounds a hopeful note. “Denver is very different now. The Olympic movement itself is very different, and the world has changed too. We don’t believe that what happened in ’72 will prevent us from winning the Games.”

Only time — and the IOC — will tell if he’s right. But while it’s true that no one likes a quitter, it’s equally true that everybody loves a great comeback.