Ski Portillo Owner King Henry Purcell

THE QUIET MONARCH OF PORTILLO

Our tale of Ski Portillo Owner King Henry Purcell begins in a magical place. It’s a night like most in the Chilean Andes. The sun has sunk over Laguna del Inca, falling prettily behind the jagged silver points of the peaks, lingering awhile in a pink alpenglow, then fading entirely to black, the great Roca Jack resting in the shadows.

The sinking of the sun is a signal for the people of Ski Portillo. Some move indoors off the decks of this imposing, all-yellow hotel. Others awake from their après-ski siestas. Still others abandon the outdoor hot pools, where a little too much liquor has loosened the lips of the Americans and Argentineans, the Europeans and Brazilians. This United Nations of skiers has gossiped raucously in these pools for more than an hour, comparing descents on The Super C and race times in the Sol de Portillo. Conversation has been a mix of Portuguese, Spanish, English; as the August sun lowers, the boasting becomes louder, then louder still.

With the day’s light gone, swimmers quiet their tongues to search out robes and scurry back to their rooms. It’s dinnertime at Hotel Portillo. One mustn’t keep the dining room waiting.

We join the hungry throng. Juan Beiza, the sturdy maître d’, stands at the leather-lined dining room entrance, a fixture at Hotel Portillo. He shows us to a round table at the right of the room; the silver gleams, starched linen napkins lie waiting. Our table, Beiza tells us, is akin to a ship’s Captain’s Table—La mesa del capitán—and the maître d’ is honored to seat us for El Capitán himself will be with us in moments.

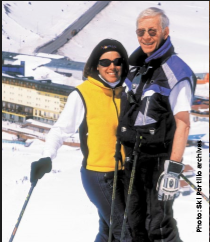

Moments turn to minutes as El Capitán, ski Portillo patriarch King Henry Purcell, wends his way into the room. Purcell is slight and silver-haired, with an air of self-containment. He is stopped at nearly every table, guests reaching out to touch his arm, shake his hand, and bid him a good evening in various languages. Purcell is gracious if not effusive. He stops to talk to one person at a time, welcoming each guest back to his hotel individually—guests who’ve vacationed at Portillo for ski season after ski season, first as children, then as parents, now as grandparents.

Purcell appears to remember every one of them..

Following behind is Henry Purcell’s life partner, Ellen Guidera, of Minnesota. Her manner enhances Purcell’s, her bursting smile offered freely. Guidera’s mane of dark hair contrasts with Purcell’s silver. They are the perfect pair, I think, as they slowly move toward our table. Together they are a team, hoteliers accustomed to warming up a room, familiar with sharing their evening meal with more than 450 people.

The couple reaches our table, finally, and Guidera offers introductions: American ski instructor prodigy Mike Rogan, now the hotel’s resident operations manager and Robin Barnes, Portillo’s personable snow school director. Purcell grimaces slightly as he eases himself into the seat next to mine—the man is pushing 80. I expect an awkward silence, but with the first words from his mouth, I’m grinning. I can’t believe my luck. This is going to be one interesting evening.

“Spider Sabich,” says Purcell, “sat at this table.”

With Henry Purcell’s opening line, I’m thrown back to the 1970s. I was just a girl with very little knowledge of professional skier and U.S. Olympian, Spider Sabich—that was, until his girlfriend, Hollywood star Claudine Longet, brandished a gun at their Aspen residence and shot him dead.

Longet’s former celebrity husband, crooner Andy Williams, stood by her innocence, and the flirtatious French starlet, who made us laugh next to Peter Sellers in The Party, walked away with a ‘misdemeanor negligent homicide.

“You’re serious? Spider Sabich at this table?” Purcell sends me a look that tells me he is almost always serious. So I settle into the softness of my seat in this storied room of Hotel Portillo, and pepper him with questions. My knowledge of ski history, the Purcell family, and skiing Portillo, is the richer for his frank answers.

Of Spider Sabich, Purcell tells me: “He was like a child. He could go too far.” He describes Sabich gone wild at the Chilean hotel; scenes of ‘70s carousing, his crazy moods and dancing on tables. Purcell seems unsurprised that the bad boy skier was eventually killed and he wonders, really, if I’d have known whom Sabich was if a movie star hadn’t killed him. He names two other pro skiers of the day and asks if I know them. No. I shake my head. His point is proven. “Too many drugs,” he says, of pro ski racing in the ’70s.

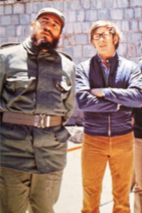

Purcell’s descriptions of Sabich’s salad days are his way of relating the role Hotel Portillo has played in skiing’s history. Ski Portillo’s Andean positioning in the Southern Hemisphere has rendered it essential summer training ground for the world’s fastest skiers. You name them, if they’ve been speedy and famous they’ve likely trained at Portillo. Purcell offers stories about Jean-Claude Killy, Stein Eriksen, Lindsey Vonn, Sigi Grottendorfer, Karl Schranz, and…Fidel Castro. Though Castro was most definitely not a skier. And through it all, Henry Purcell has been there. In black-and-white photos, this unassuming, serious, slightly awkward man (who’s a damn good storyteller) stands alongside the famous. Purcell has welcomed the world to his hotel—the quiet king of his own mountain.

How Purcell has risen to this position is a riveting story of its own. In the early 1960s, Henry was a Hilton Hotel man—a 26-year-old, Mad Men-era, Cornell graduate of hotel management who, skinny tie and all, was handily climbing Conrad Hilton’s corporate ladder. That was, until his Uncle Bob called to tell him he was about to buy a nearly bankrupt hotel and ski area…in Chile.

Uncle Bob was Robert Purcell, president of the International Basic Economy Corporation (IBEC), helmed by whom else but the Rockefellers. “He was their money man,” Purcell says, as if this explains everything. Chile was looking to get out of the government-run ski business and was putting Portillo up for auction.

“I imagine Uncle Bob was sitting around sipping martinis when he heard the hotel was for sale,” Purcell says. “He likely said to his friends, ‘Hey, you know, guys, we should buy it.’ But not, you know—not totally meaning it.”

Robert Purcell was a social skier, the nephew, explains. He loved his martinis as much as he did skiing. But when the time came for the Portillo auction, there was only one bid on the table, and that was Uncle Bob’s. So the Rockefeller’s “money man” and his partner Dick Aldrich…well, they bought Portillo.

Ski Portillo Owner Henry Purcell has written the book on all this Ski Portillo history.

Portillo, The Spirit of the Andes is a broad and beautiful tome that tells story after terrific story with delicious black-and-white photographs depicting the long gone Head-and-Vuarnet era. I spend evenings on the couches of Hotel Portillo’s lounge diving into the book’s pages. Among my favorite passages are Purcell’s depictions of his early days at the helm of the hotel, placed there by his Uncle Bob in 1961 as general manager.

About opening day, Purcell writes: “On June 15, 1961, Bob and Dick chartered a plane to fly from New York to bring a group of dignitaries, press, and ski friends to Chile for the party, among them Howard Head, Ernst Engle, Alf Engel, Merrill Hastings, Mrs. John Randolph Hearst, Ernie McCullough…”

As the story goes, in those days the only way to reach Portillo was by narrow-gauge railway, which got stuck high in the Andes… often. As bad luck would have it, an avalanche swept across the tracks just before the opening-day dignitaries’ arrival, blocking them for hours in a tunnel.

Henry and Robert had no clue what was delaying their very first guests. “Portillo only had one telephone line,” Purcell writes, “the Portillo Uno. It was a surface line and worked more or less in summer and not at all in winter.” The train finally arrived, hours behind schedule, the Hearsts and the Heads and the Hastings exhausted. But that didn’t stop Uncle Bob from throwing a rip-roaring party. The guests were received with a pisco sour.

Another favorite passage is Purcell’s description of Portillo’s hosting of the 1966 World Championships, including its opening ceremonies presided over by Eduardo Frei Montelva, then president of Chile:

“There were representatives of 20 nations in Portillo that morning. They marched in alphabetical order, Emile Allais had returned to Portillo for the games and skied down through the Garganta while a huge Chilean flag waved over the Plateau.”

Dick Barrymore caught the scene in his classic ski flick, The Secret Race. On the podium was none other than the skiing legend, Jean-Claude Killy.

Back at the table, Purcell’s love, Ellen Guidera, is happily entertaining guests with her own stories. She talks fondly of Henry’s children—Colleen, Tim, Miguel (now the hotel’s general manager) and Karen from Purcell’s earlier marriage, and Henry Richard, the couple’s own young son. Guidera likes to make her guests laugh with stories of her own family’s visits from the U.S. and their ski racing in the weekly Sol de Portillo. But this graduate of the Harvard Business School leaves the best one out—the one in which, before her marriage to Purcell, Guidera is a ski instructor fired for skinny dipping late one night in the pool at Portillo.

At our section of the table, Henry Purcell is still quietly talking only to me.

He tells me he purchased the hotel from his uncle, Robert Purcell—Tio Bob—in the ’80s, once the party lover and his partners had had enough fun growing the resort and swilling martinis. He imparts a little of what it’s like for an American to own a hotel in Chile. From his perspective, there is little corruption. “In other South American countries, if you’re stopped for speeding you slip a $20 to the officer along with your license. He keeps the $20 and gives you back your credentials…but not in Chile. In Chile, you’d go to jail for bribing a policeman.”

Purcell claims that while there have been difficult times—especially through the ’70s—the running of Hotel Portillo goes remarkably smoothly. The lodge runs at near full capacity through the entire ski season. The Brazilians come in July, North Americans in August, and Chileans arrive in September for their “spring” ski holidays. When asked how his all-inclusive ski hotel works where others have failed, he shrugs. “People come back year after year,” he says simply. “It has become tradition.”

Dinner is coming to a close and the dining room’s occupants are growing restless

for the bar, the disco, the Ping-Pong in the basement. Guest after guest stops by the table to pay respects to El Capitán. One well-fed, highly placed man in the Colombian government arrives to have a word. He’s brought his daughter, her new husband, and his grandchildren back to vacation at Portillo after a 10-year absence. Purcell nods his head as he listens to the man’s story.

“How does the new husband like it?” he asks at a break in the conversation.

The man shrugs and gestures with his hands dramatically. “He’s a banker.”

Purcell nods again. To both him and the Colombian, this appears to explain everything

The evening ends when Purcell says good night and leaves quickly though politely. It takes Guidera longer to exit the room; she’s still smiling, chatting, welcoming. Once they’ve left, I realize I didn’t ask about Fidel Castro…I rely instead on the way Purcell related the encounter in Portillo, Spirit of the Andes.

As this final story goes, Castro spent a summer day admiring Portillo’s lake and mountains. He ate lunch in the hotel’s living room, resting his pistol on a chair—and then left without it. Castro’s young Portillo waiter, Juan Beiza—now the stalwart maître d’—found the gun and rushed outside to return it.

“As he saw the group getting into the cars, Juan raised the gun and was nearly shot along with all the other spectators when very nervous security people thought that he was trying to attack Castro.”

At the end of the near fiasco, the nervous group departed, roaring away in matching blue Fiats with heavily armed guards hanging out the windows.

At the sight, I’m guessing Purcell was grateful he hadn’t countered too strenuously when Castro argued with him earlier in the visit.

The nature of their dispute? Politics? Ideology?

No, elevation. Castro had insisted that his mountains in Cuba were higher than Purcell’s Chilean Andes.

Related Posts

December 11, 2019

Fast Forward-Lindsey Vonn Article & Photoshoot

What Lindsey Vonn has been up to since…