The joys and tradition of New Hampshire skiing

in the White Mountains.

Is it possible? Is it still possible to find a place where you can ski on trails set out by the pioneers of the sport, buy custom-made ski boots, skate in the moonlight at the center of town on the public rink the parks department floods at night, and pop into the gas station and buy maybe the very best donuts in the United States? And is that a place where there is a ski shop that treats its customers with such care and skill that a skier might drive 550 miles for a tuning and a wax job? Is it possible?

Is it possible? Is it still possible to find a place where you can ski on trails set out by the pioneers of the sport, buy custom-made ski boots, skate in the moonlight at the center of town on the public rink the parks department floods at night, and pop into the gas station and buy maybe the very best donuts in the United States? And is that a place where there is a ski shop that treats its customers with such care and skill that a skier might drive 550 miles for a tuning and a wax job? Is it possible?

Well, every year I take that 550 mile drive, and it leads directly to the White Mountains of New Hampshire, where I have skied for more than a half century and where, it might be added, everyone still knows my name, and would know yours, too, if you stopped in on a winter’s day, or for a winter. In the (very) old days, Daniel Webster and Henry David Thoreau spent time here — I’d be fibbing if I tried to tell you they made first tracks — and so did the economic theorist John Maynard Keynes, who didn’t ski, but did help set the 1944 price of gold at $35 an ounce and create the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. All that happened at Bretton Woods, which is now New Hampshire’s largest ski area.

So we’ve established that there is history here, and that I have a history here, too. My history intersects with the region’s history, for I learned the lost art of the stem christiana at the (bent) knees of the veterans of the 10th Mountain Division and, specifically, under the tutelage of the grand Herbie Schneider, whose father can be said to have founded modern American skiing when he left fabled St. Anton am Arlberg, Austria, where he established one of the world’s first ski schools in 1907, to avoid the grip of Adolf Hitler, and arrived in the tiny village of North Conway, New Hampshire. Herbie, who is pictured on that storied day wearing a sharp

So we’ve established that there is history here, and that I have a history here, too. My history intersects with the region’s history, for I learned the lost art of the stem christiana at the (bent) knees of the veterans of the 10th Mountain Division and, specifically, under the tutelage of the grand Herbie Schneider, whose father can be said to have founded modern American skiing when he left fabled St. Anton am Arlberg, Austria, where he established one of the world’s first ski schools in 1907, to avoid the grip of Adolf Hitler, and arrived in the tiny village of North Conway, New Hampshire. Herbie, who is pictured on that storied day wearing a sharp

Tirolean ski blazer and a white beret, evolved into something of a Mozart of Cranmore Mountain: His simple but beautiful turns, grace personified as he cruised down the South Slope or on the tougher reaches of a trail called The Ledges, possessed the contrapuntal elegance of the late Baroque, a sonata on snow. He was known as “Zip”, a name that was emblazoned on his New Hampshire license plate, in big green letters right under the “Live Free or Die’’ slogan.

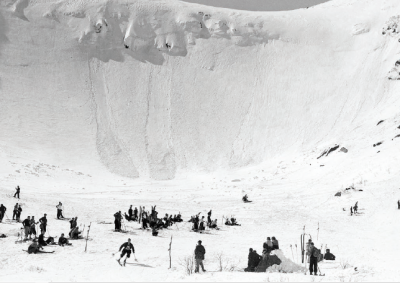

Herbie is gone now — so are Benno Rybizka, Franz Koessler, and Otto Lang, all part of the revolutionaries of American skiing. Gone, too, is Toni Matt, who, during the legendary American Inferno race of 1939, became the only person to have schussed the headwall of Tuckerman Ravine, up there on Mount Washington, the tallest peak in the Northeast. In the archives of the New England Ski Museum, a jewel of a resource planted at the base of Cannon Mountain, you will find a picture of Corporal Herbie Schneider and Lieutenant Toni Matt in their World War II army uniforms while in Colorado, there to train for the 10th Mountain Division.

Gone, too, is Dr. William Duprey, the versatile local physician who often, on the very same day, delivered a baby and set a few broken legs (my brother Pete’s was one of them) in the whiteclapboard hospital on North Conway’s main street. And gone, as well, is the Skimobile, a rackety contraption that a local handyman and storied tinkerer, George Morton, fashioned on the side of Cranmore. For more than a half century those red-and-green cars climbed gently to the top of the mountain. You had to take your skis off, and sometimes you felt as if you might tumble off the track, but for decades there was no sturdier symbol of the ski life of the East than those Skimobile cars, the hosts of the highways of the hills. For me, as for so many others, those cars were the gateway drug to the high-speed lifts of today.

Gone, too, is Dr. William Duprey, the versatile local physician who often, on the very same day, delivered a baby and set a few broken legs (my brother Pete’s was one of them) in the whiteclapboard hospital on North Conway’s main street. And gone, as well, is the Skimobile, a rackety contraption that a local handyman and storied tinkerer, George Morton, fashioned on the side of Cranmore. For more than a half century those red-and-green cars climbed gently to the top of the mountain. You had to take your skis off, and sometimes you felt as if you might tumble off the track, but for decades there was no sturdier symbol of the ski life of the East than those Skimobile cars, the hosts of the highways of the hills. For me, as for so many others, those cars were the gateway drug to the high-speed lifts of today.

That’s what’s gone. What remains, besides the crisp cold of New Hampshire’s White Mountains, are views and vistas both invigorating and inspiring, stirring painters such as Thomas Cole (who wrote in a sketchbook of “the voice of winter in this howling blast’’) and Albert Bierstadt, along with illustrators such as William H. Bartlett, whose prints are prized today, and the printmaking firm Currier and Ives, whose images still are prominent in calendars year after year. “Visitors are never disappointed in these mountains, however grand their anticipations may be,’’ wrote Harper’s Monthly in August 1877, “and thousands of tourists of the most fashionable class, who are weary of all other pleasure resorts … visit them again and again, and always go away satisfied.’’ (Sometimes, of course, they do not go away at all. You’ll find me here on nearly every vacation, and imminently in retirement.)

“Visitors are never disappointed in these

mountains, however grand their anticipations

may be …” — Harper’s Monthly

And what remains is a tradition of skiing that dates to the days when the ski trains left New York and Boston and disgorged the gorgeous and the gregarious at the heart of North Conway for ski weekends that live on in legend. Most of them walked, skis on their shoulders, the final mile to the ski area.

That North Country tradition includes a palette of skiing that runs from the relaxing to the rugged. There are a fistful of ski areas besides Cranmore, Cannon, and Bretton Woods: mighty Attitash Mountain, with its breathtaking views, and formidable Wildcat Mountain, where, when you turn the corner on the Polecat trail, a family favorite for generations, you might think your right shoulder could brush the summit of Mount Washington. It is only an illusion — a winter mirage, you might say — but it will linger with you for years. Follow the road through Jackson’s covered bridge, Honeymoon Bridge — perhaps the most photographed bridge in the world, maybe not counting the Brooklyn Bridge — to Black Mountain and you’ll return to a bygone era. The T-bars are gone, replaced by chairlifts, but the old-time esprit remains.

The rooms of Christmas Farm Inn & Spa bear the name of Donner and, for the more adventurous skier, Dasher.

That tradition includes food — and drink. The contemporary North Conway includes the de rigueur coffee shop — the Metropolitan Coffee House, known as the Met, inside an old bank building — but the difference is that outside the shop rests one of those old Cranmore Skimobiles. And yes, there is a microbrewery, and it produces a beer called Tuckerman’s, which is the name of the storied ravine on Mount Washington that Toni Matt conquered and that persists as the great springtime test of skiing mastery in the Northeast. The best burger in the area is at Black Cap Grill, which is the  name of the mountain beside Cranmore; my wife and I climbed to that peak last summer, hiking across the valley in the hope we might see snow on the summit of Mount Washington. You’ll need your fat pants if you venture into Vito Marcello’s Italian Bistro in North Conway. And the donut I rhapsodized over in the beginning of this elegy? That’s at Sid’s Valley Food & Beverage, a gas station right at the center of North Conway. I prefer the chocolate glazed. Sid’s gives new meaning to the term “fill up”.

name of the mountain beside Cranmore; my wife and I climbed to that peak last summer, hiking across the valley in the hope we might see snow on the summit of Mount Washington. You’ll need your fat pants if you venture into Vito Marcello’s Italian Bistro in North Conway. And the donut I rhapsodized over in the beginning of this elegy? That’s at Sid’s Valley Food & Beverage, a gas station right at the center of North Conway. I prefer the chocolate glazed. Sid’s gives new meaning to the term “fill up”.

That tradition includes meticulous attention to your ski equipment. There may be another ski shop in the United States, but to my mind the only one worth visiting is Stan & Dan Sports. Some days I’ll wander in there and spend an hour, chatting with Stan Millen about the news and watching Dan Lewis do wonders fitting my wife — veteran, or victim, of two toe surgeries — with ski boots. If mama’s feet aren’t happy, nobody’s happy. If it’s a custom-fit boot you require, a half mile away is the studio of Merlin Strolz, descended from the craftsmen cobblers of Lech, Austria, who have designed ski boots since 1921. The likely cost, which includes a two-hour, by-appointment-only fitting session: around $1,200.

And that tradition includes toasty lodges like the Cranmore Inn, right there on Kearsarge Road, which has been playing host to visitors since the Civil War, as well as sprawling resort hotels like the Omni Mount Washington Resort, which was where Keynes (and Henry Morgenthau Jr. and Dean Acheson and scores of other global luminaries) gathered to plan the post-war economy, and where my wife and I split an unforgettable lobster roll a few months ago. On your visit, bring a long novel for the long white afternoons in front of the fireplace, stuffed as it is with birch branches. The jigsaw puzzles are there, too. It wouldn’t be a ski lodge without them.

If you pick up the guest book at the Christmas Farm Inn & Spa, tucked on an incline in the village of Jackson, you will see, along with mine, in primitive script on January 4, 1964, some familiar names. It’s a hall of fame of (mostly) failed presidential aspirants.

That’s because no presidential campaign in the New Hampshire primary is complete without at least one night in that inn, whose rooms bear the name of Donner and, for the more adventurous skier, Dasher. (Note to potential guests: The room bearing the name of Cupid sleeps only two. But of course it does.) The place verily screams with stories, including the time, in the 1992 campaign, when an independentminded political wife in a room without a telephone sent word that she wasn’t inclined to leave her eiderdown comforter to take a call downstairs from her husband. The night manager advised President George H.W. Bush that maybe it would be best if he called back in the morning.

That’s because no presidential campaign in the New Hampshire primary is complete without at least one night in that inn, whose rooms bear the name of Donner and, for the more adventurous skier, Dasher. (Note to potential guests: The room bearing the name of Cupid sleeps only two. But of course it does.) The place verily screams with stories, including the time, in the 1992 campaign, when an independentminded political wife in a room without a telephone sent word that she wasn’t inclined to leave her eiderdown comforter to take a call downstairs from her husband. The night manager advised President George H.W. Bush that maybe it would be best if he called back in the morning.

Years ago, former Governor Bruce Babbitt of Arizona, a devoted skier, told me of his devotion to this region. “There you are,” said Babbitt, who campaigned for president in these hills, losing the Democratic primary in 1988 but never losing his love for the Granite State, “teetering on the edge of Canada in little towns soaked in tradition, full of people with a totally independent view of life.” There you are.